Defining privacy from first principles: observation & disturbance

In order to build a privacy approach for any brand, we must first define what we mean by privacy.

Let’s start broadly; privacy, in the absolute state, is where one is not observed or disturbed by other people; free from public attention.

Now let’s apply that to digital advertising. Wait it doesn’t apply. Because absolute privacy in a digital advertising context is a fallacy.

The nature of software is such that there will always be some form of ‘trail’ from a user’s activity. A programme needs to know some things to function; what have you just done, what are you currently doing. Designing software in any other manner is the preserve of a spy agency, not an advertising one. So if software must observe you to some extent in order to function, that data has to exist and be collected and processed. Hence the focus must be on who has that data.

And if we think back to before the internet, we were fine with different phone numbers on TV & print ads, used to determine which one had driven a call to the call centre. Marketing has always strived towards measurability to justify itself. Zero observation and disturbance isn’t going to work.

So privacy, in this context, is not an absolute and its unlikely that it ever will be. Rather it’s a balance. Most people will tolerate some observation, and disturbance, if they get value from it.

Do we really need all that data though?

Some observation & disturbance is very different to the notion of ‘surveillance capitalism’, an emotionally charged description of how the modern digital economy works.

And this argument has some high-profile proponents. Tim Cook, CEO of Apple said in January 2021, “Technology does not need vast troves of personal data, stitched together across dozens of websites and apps, in order to succeed.” He also pointed out “Advertising existed and thrived for decades without it”.

Neither statement is wrong. But they are incomplete arguments.

Technology can operate without an identity or interest graph to power it. And you can advertise without leveraging any personal data. However, both technology and advertising can do much more, for many more people, when people-related data is added. It’s called customer experience.

Apple’s position is clearly self-serving, given the growing scale of their services / ads business, plus their ambitions in the health vertical. But ironically it also illustrates the point around customer experience. Check which data your iPhone collects; usage, location, financial, biometric, health, etc. All to make better products & serve you better, of course.

But why is there a separate, harder to find, opt-out for ‘personalised’ Apple Ads, versus the obvious ‘tracking’ opt-in for other apps? It’s because customer experience starts from the first interaction you have with a brand and spans every touchpoint you subsequently encounter. Data helps to make that experience better, and Apple want that data.

It’s tempting to debate the semantics of Apple’s framing. But it’s more constructive to think about the broader points it raises: what marketers can do with digital data and what they should do.

What marketers can do, and what they should do, with data

What marketers can do with digital data is easier. Here, it’s helpful to consider the analogy that ‘data is sand’; an individual grain isn’t much use, but lots of grains can be very helpful.

Marketers want lots of data, but they don’t want to hack your bank account’s PIN; this isn’t much use to them. But they are interested in which segment you fit into, and how people like you respond to a message or experience. Such aggregations are better for marketers – making scaled campaigns viable – and better for your privacy.

This is often lost in talk of 1:1 marketing and personalisation. But any ad must scale or its economics wouldn’t make sense. Digital has helped here, and not just in its ability to target based on observed behaviour. Dynamic ads can display more relevant copy, imagery, links and more. But these are picked from a library of tens or maybe hundreds of variables, not millions. So the people targeted will see a very similar, if not the same, ad. Even in direct email marketing, it’s still a template with a few variables changed. This is not too different in principle from postal marketing based on loyalty card data. It’s hardly breaking news.

It’s better then to think of marketers making tailored, not bespoke, ads. There are underlying designs, which are adjusted on what is known when the ad is shown. Each ad isn’t created from scratch.

What should marketers do with this capability? This is a much broader question, but three principles seem pertinent:

- Be clear about the role data plays in the organisation’s commercial model

- Take a privacy stance to design good data-value exchanges

- Think about data usage in marketing analysis and activation slightly differently

The role of data in a company’s commercial model

Every organisation uses data, but its commercial role can vary dramatically. Businesses can be wholly, partially or non-ad-funded. Facebook doesn’t sell users’ data, rather it sells the opportunity to advertise against that data. This is their business model; 98% of revenue comes from ads. At the opposite end of the spectrum, Netflix doesn’t sell traditional TV ads. Revenue instead comes from subscriptions (and perhaps in the future less traditional ads & shoppability). So fundamentally, data plays a different role within the organisation – optimising production and recommendation. In the middle of these two extremes sit businesses such as the New York Times, which balance subscription revenue (67%) with ad revenue (22%). Data fuels both these income streams of course, but it is monetised differently.

Designing transparent data-value exchanges

Those approaches also illustrate well-judged data value exchanges. Each businesses’ customers understand what they get in return for giving data to that company. Facebook users get a free service but see tailored ads. Netflix users pay monthly, don’t see ads, and get recommendations. New York Times readers pay and see ads, but that subsidises the subscription cost and the NYT takes a very public privacy stance about what should & shouldn’t happen in digital. By entering into such exchanges transparently, firms can build sustainable revenue from willing audiences, because there is value to the user.

Data usage in marketing analysis and activation

Finally, marketers should revisit how they use data to understand consumer behaviour and to respond to it. There are some marketing analyses that are only possible with very granular data. Multi-touch attribution is a good example; you must build an ‘event stream’ at the individual level to accurately model which media were most effective in driving a particular action, such as a sale. Can you still obtain such data, or are you going to need to find a different way? Does your CDP help, or is a data clean room an option? Does the data clean room give you options, but force platform-specific analysis? If so, are models which use aggregate data a useful supplement? And, was this true long before cookies were phased out and privacy measures implemented? On the activation side, how might you redesign the customer journey to either capture data directly, or lessen the need to switch between platforms? What other factors – creative, loyalty, commerce – should you be thinking about to suit the new data landscape & rules?

The variable which marketers will struggle to act on in advance is regulation. And government-imposed rules can change the basis of the decisions outlined above. But if brands plan in the best interests of consumer privacy; balancing observation & disturbance with the experience users get in return, then they will be well-placed to adapt to such legislation.

Illustrating privacy

That’s a lot to think about. So it’s helpful to consider some heuristic ways to assess your privacy stance.

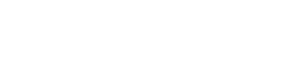

The diagram above illustrates the 3 examples used earlier, on a privacy curve, to capture the assertion that privacy in digital marketing is a balance, rather than an absolute.

A purely ad-funded model sits in the bottom left (lower cost, lower privacy). A pure subscription model sits in the top right (higher cost, higher privacy). That the line doesn’t go to zero on either the cost or privacy axis is intentional. This is in keeping with the argument that total privacy isn’t viable in digital advertising. Moreover, there’s never a zero cost to the consumer; you ‘pay’ for free services with your data and or attention. Regulation could shift the curve or change its shape. Platforms can exist ‘off’ the curve for a period, especially as they scale, but will tend towards it as they mature as a viable business.

When will people share data?

Simply picking a point on the privacy curve where a brand wants to be isn’t enough. It must offer a data value exchange that appeals to its intended audiences.

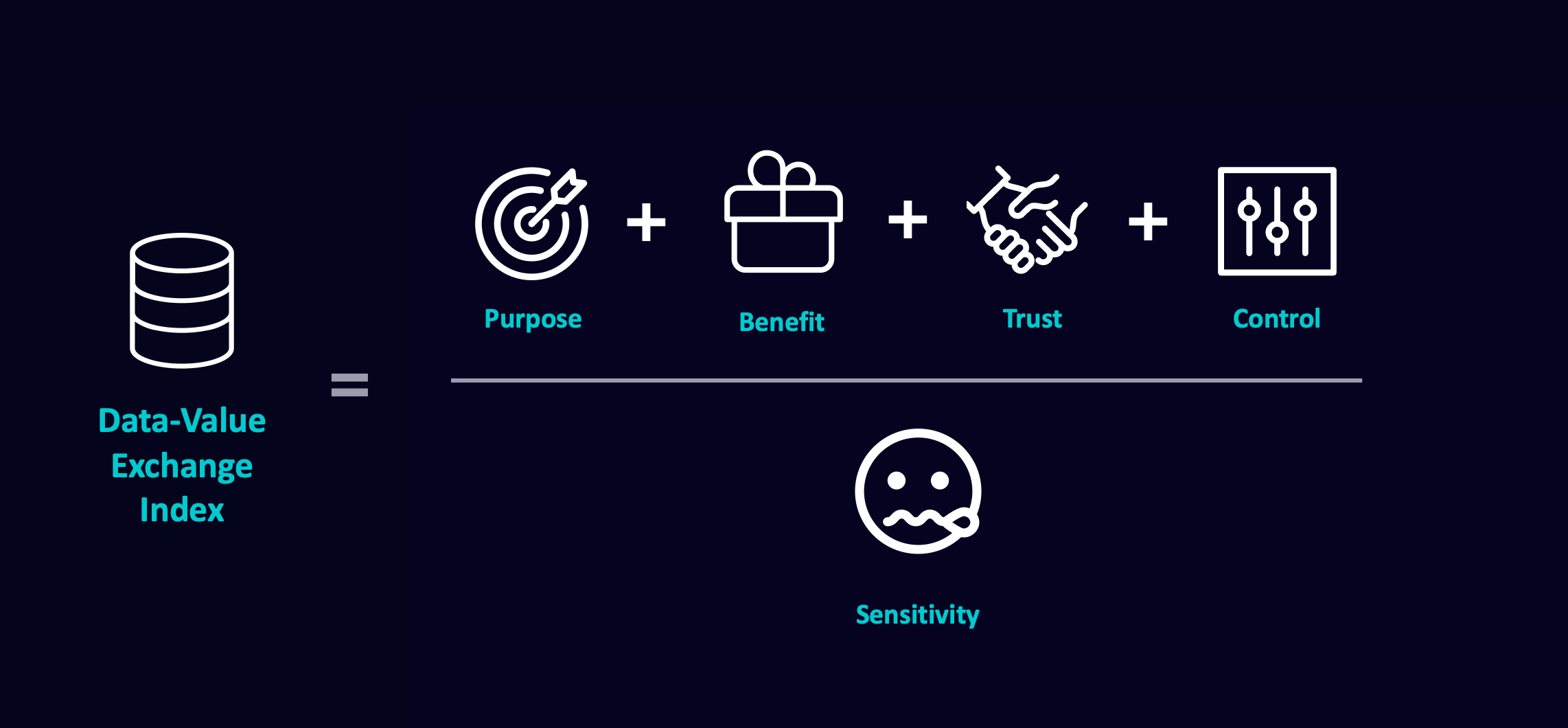

What will encourage people to share data with an organisation? The trade-off is a balance, as illustrated below:

A higher ‘index score’ suggests a more valuable data exchange. If you score each of the factors from 1-5, you get an index between 0.8 and 20 to judge its likelihood of success.

This goes further than how privacy is set out in the EU’s GDPR, which says you must “empower your users to make their own decisions about who can process their data and for what purpose”.

Purpose is shared with the GDPR and is clearly critical – it defines the premise of the exchange; what is going to happen if the consumer accepts. Separating out Benefit to the customer is helpful though, where it forces a brand to think from the consumer perspective. Whilst purpose might suit your ends, does the benefit suit the customer? It is, after all, an exchange.

Trust is synonymous with Brand, but should also encapsulate the broader industry vertical. You might be a great bank, but if there’s a financial crisis, will any bank be fully trusted in the short term? Are other 3rd parties also going to be involved?

Control picks up on the GDPR point around user empowerment, but implies an ongoing set of choices, rather than a one-off transaction. Any brand looking to optimise customer lifetime value should keep this point in focus.

Finally, by dividing these four ratings by Sensitivity, the data-value exchange index is calibrated to the nature of the data involved. The more sensitive the data, the lower the index figure. This helps quantify the ‘their data’ point from the GDPR description.

Having refined the nature of the privacy debate, what next?

Brands which have understood the nature of privacy in a digital marketing context can then seek to address the challenges the industry faces. We summarise these as; surveillance, security, silos, sense & sustainability.

In the next instalment of this privacy series, I’ll cover more on privacy in digital marketing. Stay tuned!